- Home

- Gordon Harper

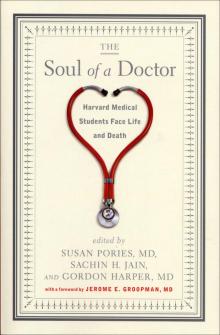

The Soul of a Doctor

The Soul of a Doctor Read online

The Soul of a Doctor

Harvard Medical Students Face Life and Death

edited by SUSAN PORIES, MD, SACHIN H. JAIN, and GORDON HARPER, MD

foreword by JEROME E. GROOPMAN, MD

Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill 2006

WHEN THEY ASK ME, AS OF LATE THEY FREQUENTLY DO, HOW I HAVE FOR SO MANY YEARS CONTINUED AN EQUAL INTEREST IN MEDICINE AND THE POEM, I REPLY THAT THEY AMOUNT FOR ME TO NEARLY THE SAME THING.

William Carlos Williams

Contents

FOREWORD

PREFACE

INTRODUCTION

I. COMMUNICATION

More Like Oprah, Alaka Ray

Learning to Interview, Joe Wright

The Difficult Patient, Anh Bui

No Solution, Keith Walter Michael

An Emotional War on the Wards, David Y. Hwang

Giving Bad News, Amanda A. Muñoz

Straight Answers, Aari Wassner

Of Doors and Locks, Matt Lewis

Reclaiming the Lost Art of Listening, Mike Westerhaus

II. EMPATHY

Inshallah, Yetsa Kehinde Tuakli-Wosornu

The Twelve-Hour Child, Wai-Kit Lo

On Saying Sorry, Alejandra Casillas

Coney Island, Yana Pikman

The Naked Truth, Joseph Corkery

Losing Your Mind, Esther Huang

Breathing the Movie, Joe Wright

Donor, Kimberly Layne Collins

Living with Mrs. Longwood, Rajesh G. Shah

III. EASING SUFFERING AND LOSS

Not Since 1918, Kedar Mate

The Tortoise and the Air, Vesna Ivančić

“Looking at the World from Far Away,” Amy Antman

Early-Morning ED Blues, Kim-Son Nguyen

Zebras, Hao Zhu

The Last Prayer, Joan S. Hu

Limitations, Greg Feldman

Autopsy, Christine Hsu Rohde

It Was Sunday, Tracy Balboni

Transitions, Kristin L. Leight

Imagine How You’d Feel, Andrea Dalve-Endres

Squeeze Hard, Brook Hill

Code, Joan S. Hu

The Heart of Medicine, Annemarie Stroustrup Smitn

IV. FINDING A BETTER WAY

Black Bags, Kurt Smith

A Murmur in the ICU, Joe Wright

Rewiring, Mohummad Minhaj Siddiqui

Taking My Place in Medicine, Antonia Jocelyn Henry

Identity, Alex Lam

The Outsider, Charles Wykoff

Raincoat, Anonymous

Physicians or Escape Artists? Sachin H. Jain

The Healing Circle, Chelsea Flanagan Elander Bodnar

Strong Work, Walter Anthony Bethune

I Would Do It All Again, Gloria Chiang

Growing Up, Vesna Ivančić

EPILOGUE

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Foreword

PHYSICIANS OCCUPY A UNIQUE PERCH. They witness life’s great mysteries: the miraculous moment of birth; the perplexing exit of death; and the struggle to find meaning in suffering. An immediate intimacy occurs between doctor and patient. There is no corner of the human character that cannot be entered and explored. A physician’s experience goes far beyond the clinical, because a person is never merely a disease, a disorder of biology. Rather, each interaction between a doctor and a patient is a story.

It has been said that all of literature can be divided into two themes:; the first, a person goes on a journey; the second, a stranger comes to town. This is, of course, terribly simplistic, but there is a core of truth in it. And it is also true that narratives of medicine meld both these themes. A person goes on a journey: that person is the patient, but accompanying him on the voyage is the doctor. A stranger comes to town: that stranger is illness, the uninvited guest who disrupts the equilibrium of quotidian life. Where the journey leads, how the two voyagers change, and whether the stranger is ultimately expelled or in some way subdued give each narrative its unique drama. During the course of diagnosis and treatment, we witness moments of quiet triumph and abject failure, times when love is tested and God is questioned. There is pain and there is pleasure, joy and despair, courage and cowardice.

The essays that follow touch on these aspects of the human condition. They are distinguished by the fact that their authors are in a special limbo, no longer lay men and women, but not yet certified physicians. They are in their first encounter with the sick, learning both the science and the art of medicine, and so write about the dilemmas of their patients and the conflicts within themselves with original candor. We are paradoxically reassured by their self-doubt and deep fears, because the best physicians are those who grow to be acutely self-aware. We are also heartened by their emerging ego, for all doctors must have sufficient ego to stand at the bedside in the midst of the most devastating maladies and not flinch or retreat.

I did not have the opportunity to write, or indeed to deeply reflect, during my days as a student. Thirty years ago, there was little time or attention given to exploring the experiences and emotions of trainees during their first days at a patient’s bedside. The emphasis was fully on acquiring knowledge, both scientific and practical; performance was gauged on how well you could explain a patient’s disease and its possible treatments. Certainly the primary imperative of a physician is to be skilled in medical science, but if he or she does not probe a patient’s soul, then the doctor’s care is given without caring, and part of the sacred mission of healing is missing.

Similarly, three decades ago, there was scant focus on language, the spoken and unspoken messages we gave our patients and shared among ourselves. A doctor’s words have great power, received by the sick and their loved ones with a unique and often lasting resonance. Alas, we as students quickly abandoned normal speech and took on the formulaic phrases of the wards: “Your presentation is consistent with myocardial ischemia.” “Excision of the adenocarcinoma is optimally done according to our protocols.” “Remission rates can be as high as fifty percent with semiadjuvant chemotherapy.” Adopting stylized speech was part of entering the guild of medicine and served its purpose of shorthand transmission of information among professionals. Such communication was seen as definitive and complete and was delivered with good intentions. But all too often it was obscure in meaning to a layperson and served to truncate or even end further conversation. It also worked to limit our examination of the values and beliefs of the people before us, people seeking a solution that made sense to them as individuals. We needed to explain what all this technical information meant, not only for their heart or lungs or kidneys but for their soul. The diagnosis and the treatment were just starting points to enter into a dialogue about the emotional and social impact of their condition and what we were proposing to do about it. Alas, that dialogue rarely occurred.

Writing about our experiences and the experiences of our patients forces us as doctors to return to a more natural language, one that, while still clinically accurate, is truer to feelings and perceptions. Such writing helps us step down from the pedestal of the professional and survey our inner and outer world from a more human perspective.

There has been a growing shift in the culture of medicine, and the experiment in writing is part of that change. The experiment has already proved its worth, based on what we read here. The contributions in this volume cover a wide swath of experience and emotion among a diverse group of students at a formative moment in their lives. What they learn, and what they still seek to learn, serve as lessons for us all.

JEROME E. GROOPMAN, MD

Preface

I HAVE BEEN TEACHING STUDENTS in the Harvard Medical School Patient-Doctor course for nearly a decade. It has turned out to b

e very different from the classes I was used to teaching and ultimately a life-changing experience. I routinely stand in front of large groups of medical students and give lectures on the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer. But in the Patient-Doctor course, there were just ten students in each class, and the teachers sat around a table with the students, rather than standing behind a podium. There was a syllabus, of course, but many times we left the assigned readings behind to talk about students’ experiences on the wards. In the beginning, I wasn’t the best teacher. It was only as I talked less and listened more that I began to appreciate how much the students could teach me. As a result, I’ve became not just a better teacher, but a better doctor and person.

In teaching hospitals, medical students learn as much from their patients as they do from their professors. The students learn by spending time with their patients, writing down the patient history carefully, documenting all the details of a case, and performing a full physical exam. Because they are not yet doctors, the form unique relationships with their patients, helping them to understand their illnesses and treatments and bringing their concerns and issues to the attention of the residents and doctors. Being close to the patient and new to the hospital world, the medical student can serve as a valuable liaison between the two. While the doctor might be limited to a fifteen-minute visit, the student is often the only one to sit with patients, getting to know them and their families as people, which may be the most valuable tool for working through difficult decision-making scenarios. The student is also often the only one on the patient care team with the time to read every page in all the old charts and may find an important fact that has been overlooked. I’ve learned to listen carefully to my students for everything they see and hear.

In addition to talking about their experiences on the wards, students in the Patient-Doctor course are asked to write about those experiences as well. This selection of essays is the product of those reflections. While some of the students will undoubtedly follow in the footsteps of successful physician-authors, most are simply writing from the heart about their profound life experiences in their new word of medicine. I am very proud of the and moved by our students’ honest writing—all of which provides unique insight into how young men and women grow into their chosen profession as physicians.

Yet as many of these essays demonstrate, the medical students’ largest challenge is not I mastering clinical or scientific principles but rather in learning how to become empathic physicians. There’s an important difference between sympathy and empathy. While sympathy implies pity, empathy denotes understanding. Learning to meet patients where they are and “walk with them” requires nonjudgmental respect and appreciation for what the patient is going through. The kindness and compassion displayed by a truly empathic physician embody the bedside manner that patients value most. Maintaining empathy while upholding professional boundaries and delivering care is a delicate balance for students to learn to negotiate.

Empathy is a difficult quality to teach by any means other than example, both positive and negative. Students need to observe experienced physicians as they sit at the bedside, hold the patient’s hand, explain things carefully, examine the patient gently and respectfully, answer questions thoughtfully, comfort the family, help a patient find a comfortable position in bed, ensure adequate pain medications have been ordered, and finally help with plans for going home

But experienced physicians can also learn from students. Unfortunately, as some of the essays here demonstrate, things don’t always go as planned, and medical students will undoubtedly also see what happens when providers don’t pay full attention: clues are missed, patients aren’t always handled sensitively, bad news is delivered inappropriately. Seeing ourselves through the students’ eyes shows us how much further we need to go.

I’d learned in my training that surgeons are expected to be the “captain of the ship” in the operating room and must be decisive and purposeful, which can make them seem brusque. The role of a surgeon is now evolving into “team leader” rather than “captain,” but having a thick skin is still necessary for survival in a tough surgical residency and fellowship. These characteristics don’t always endear them to medical students. As a small illustration of how students view surgeons, while editing this book of essays, I suggested that one of the student authors change his description of feedback he received after a woman from “a surgical comment” to “a brief comment.” He wrote back that he really liked the word surgical because “this is the way surgeons really speak: terse, pointed, surgical statements.” He had a good point. And as a young surgical attending, I began to realize that the sort of efficient and technically proficient surgical persona required in a chief surgical resident was not entirely healthy and could in fact interfere with my growth as a person and an effective practitioner and teacher.

As a woman and a dedicated breast surgeon, I know that empathy and compassion are as important to my daily work as technical skill, clinical knowledge, and efficiency. The students’ observations have helped me see the medical world anew, keep in closer touch with our patients’ points of view, and revisit the reasons I went to medical school in the first place. I am very thankful for the opportunity.

SUSAN PORIES, MD, FACS

Introduction

MY MOST TRYING WEEKS OF MEDICAL SCHOOL were spent in the emergency department at the Massachusetts General Hospital. I took call with the surgical residents, which meant I worked twenty-four-hour shifts every other day. In addition to suturing minor lacerations, I participated in traumas. When a trauma patient arrived—often a victim of a gunshot, stab wound, or motor vehicle accident—I sent blood to the appropriate laboratories. It was a minor role, but it provided a front-row seat to human tragedy that one otherwise only hears about on the evening news. It was the kind of excitement that draws some of us to medicine in the first place.

Midnight on my third night on call, I was summoned: “Trauma team to trauma.” I collected all the necessary vials and hurried to the trauma bay. The patient had arrived, and there was an urgency to the situation that I had not seen before. On previous nights on call, our patients had ended up walking out of the emergency room nearly intact. The patient on the gurney was different. Seventy-three years old, she had been struck by a car traveling sixty-five miles an hour and thrown fifteen feet. Her hips were shattered. She was losing blood faster than we could replace it.

My surgical resident called out for me to obtain a medical history from her family. He was going to take her to the operating room. I ventured out to the waiting area and saw our patient’s eighty-year-old husband. I asked him to join me in a private room and tried to be concise.

I said, “Sir, I’m very sorry, but your wife is going to the operating room. Her condition is unstable, and we need some information from you about her medical history. Does she have any medical problems or take any medications?”

I had never before seen an eighty-year-old man cry. He sobbed, “No, no, no, no,” over and over again. ”It’s my birthday. We were just getting off the bus after going to the casino. She doesn’t listen to me. She just runs ahead with a mind of her own, and see what happened! Tell me she’s going to be OK. Tell me!” Uncomfortably I placed my hand on his shoulder and listened to him cry, reminding myself to press on with my questions. Except for hypertension, she did not have any medical problems and was not allergic to any medications. She had been in near-perfect health. They had been married for fifty-five years.

Mrs. M. made it through the early morning but died on the operating table. There was talk of salvaging some of her organs for transplant. I went home and crawled into bed. I had been awake for twenty-seven hours. I could not sleep.

When I started medical school, I did so with the unwavering belief that I could save lives, ease suffering, befriend my patients, and go home satisfied every day. That was, at least, how I justified the costs and length of training. I was maddeningly naive about what I was about to experience.

The political scientist Michael Walzer has written extensively on the phenomenon of “social criticism.” The ideal social critic, he argues, is someone who is embedded in a society but able to apply external values to critiquing it. The medical student represents the Waltzerian ideal. Knowledgeable about medicine but still idealistic, the medical student has not yet been changed by the norms of practice. He may be more able than others to reflect thoughtfully on the health care system and uncover defects in care—and more sensitive to the effects that these defects have on patients.

This book, a compilation of essays by fellow students at Harvard Medical School, chronicles our transformation as we begin to confront the reality of taking responsibility for the health and lives of patients. Many of the stories here will inspire confidence in the medical profession’s youngest members. Others will raise questions about how we care for our patients. Grouped under four themes—communication, empathy, easing suffering and loss, and finding a better way—the essays collectively reflect the complexity of emotions and personal challenges that we experience as we begin to care for the ill. At their core, these essays provide a glimpse into the young physician’s hopes for, and misgivings about, both themselves and the profession.

The Soul of a Doctor

The Soul of a Doctor